Working your core, balance and a host of different muscle groups, plus honing concentration levels and getting you outside, is what slacklining is all about. And then there’s highlining… By Megan Banner

Slacklining is not really like tightrope walking, except for the mental image: a person balanced on a narrow strand between two anchors, trying to make it across while intently focused on a point at the far end.

So, okay, I guess it’s more like tightrope walking than, say, rugby is like tightrope walking. Perhaps it’s better thought of as a younger, cooler sister sport. The difference is that, while a tightrope is a taut, static cable, a slackline is dynamic. The flat webbing, which is normally one or two inches wide (yes, it’s measured in inches), bounces, flexes, and reacts to every movement, and counterbalance comes from constant micro-adjustments in the walker’s upper body. It engages a completely different set of muscle groups than with tightrope walking, and it requires a different sort of mindset.

Progression in the sport of slacklining mirrors human physical development more than any other activity I’ve ever encountered. The learning curve is steep, the challenge equally mental and physical, and mastery may take years. At first, just like a one-year-old child, you step on to a slackline, wobble a bunch, and fall off. You step on again, take half a step, and fall off. It’s really maddening. Finally, after a long, dedicated effort, the right muscles develop, the balance settles in, and you’re able to cross your first five-metre line.

From there, the line is your oyster, as they say, as the sport has branched into multiple varieties in recent years. There is longlining, which requires incredible physical stamina as you attempt to cross lines longer than 30m; lowlining, akin to the slow, flowing movements of yoga; and tricklining, a high-energy tangent of lowlining involving jumps, spins, and even flips. Then, to kick the mental intensity up a few notches, there’s highlining: this entails walking a line stretched between anchors far above the ground.

All of these disciplines were on full display recently at the annual Rocklands Highline Festival in the Western Cape’s Cederberg Mountains. Rocklands is a vast expanse of eroded sandstone and sedimentary rock, contributing to its reputation as a world-class rock climbing venue.

The festival first kicked off in this stunning lunaresque setting in 2014, when a group of highline enthusiasts wanted to expose a wider audience to the sport in a safe and controlled way. Although slacklining in general has exploded in popularity across the globe, there are few active highliners in South Africa, and there’s been very little recent growth in the community. Slacklining simply involves wrapping some webbing around two trees, but it takes a substantial amount of gear and knowledge to safely rig a highline. It is a difficult sport to penetrate, both physically and logistically, so to have an opportunity to try as a novice is an incredible privilege.

And, as it turns out, it’s an opportunity that’s attractive to quite a diverse crowd. At first, many slackliners came from a rock-climbing background (the sport originated in Yosemite Valley in the US in the 1960s and ’70s), and as a climber myself, I notice some obvious overlap between the two sports. However, the Rocklands Highline Festival is testament to the fact that slackers are no longer fed from a single stream: I met flow artists, unicyclers, gymnasts, surfers, mountaineers, and plenty of people for whom slacklining itself was the main event! What all of them seem to have in common: an attraction to balance (literally and figuratively), and love of the outdoors.

So, did I muster up the courage to try out the highline? I did! Was it 15m long, rigged between rock buttresses 20m off the ground? Yes. Yes it was. And, how did it go? Well, for some context, I’ve been a ‘casual’ slackliner for several years. I can walk a 10m lowline back and forth, and am just at the point where crazy tricks such as ‘turning around’ and ‘crouching down’ don’t seem like superhero skills. But a highline, as I quickly realised, is a different universe. The lines have to be long, and the longer the line, the more it moves. You have to stand up from sitting in the middle, unsupported. And it’s impossible, even without any declared fear of heights, to forget that there’s nothing but open space beneath you. So my attempt lasted about 30 minutes. That’s 30 minutes of sitting on the line, placing a foot, weighting it slightly, and then suddenly flying off into the air, to the end of the safety rope connected to my harness. From there, it’s a sort of acrobatic wrestling match with the line to get back on top of it, wait for my heart to stop trying to punch its way out of my chest, and then repeat. After half an hour, I was exhausted, and could already identify maybe 75 muscles I knew would be sore the next day.

One of the best parts of trying was learning exactly how much it takes to be a good highliner. The line I bounced around on was a short ‘beginners’ rig, and the longest at the festival stretched over 60m. It’s pretty hard to appreciate from the ground what a truly absurd accomplishment it is to fully walk a 60m line. I know those few who were capable had spent eons training, and slowly progressed to longer and longer lines. One of the best highliners in the country, a young Capetonian named Andy Court, admits he was ‘addicted for a few years’: ‘It took quite a lot of time to get to my current level. I walked a lot, trained on longlines, highlined a bunch and did a lot of research into the sport’. And after giving it a whirl myself, I have no problem believing what he says. But, as demonstrated by that weekend, there is no reason not to get out on the line anyway.

Flailing around for a while is all I managed, but despite that, it was an exhilarating experience. I felt totally free on the line, completely engrossed in the challenge of balancing, and intoxicated by the fact that, in that moment, nothing else in the universe mattered. I can’t wait to chase those feelings again at next year’s event, even though Andy also happened to mention that ‘it’s hard to progress if you do the sport once a year at the festival’. So I guess I will not be recruited for the Olympics anytime soon, but flailing isn’t such a bad thing, is it?

FAST FACTS

- The current highline world record is 610m.

- The company SlackGear makes and sells slacklines right herein South Africa.

- The Rocklands Highline Festival is one of dozens held around the world each year.

Photography Megan Banner, Antigravity photography

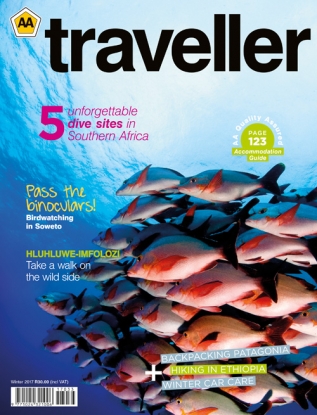

(This article was first published in the winter 2016 issue of AA traveller magazine)